TRADITIONAL IRISH PUB - CASTLETOWNBERE, BEARA PENINSULA, WEST CORK, IRELAND

Daughters whose fathers shared the barbarity of prison camps – and the horrors of A-bomb devastation

* Connie Froude with Adrienne MacCarthy at MacCarthy's Bar, and left, Connie's father Larry O'Sullivan, who came from Youghal, Co Cork, and who was in the same Japanese prisoner-of-war camp as Dr Aidan MacCarthy when the A-bomb was dropped on Nagasaki in August 1945.

The daughter of Navy man Larry O’Sullivan, who sang the praises of Dr Aidan MacCarthy for saving his arm from amputation in a Japanese prisoner of war camp in 1945, made a ‘pilgrimage’ from the UK to visit Dr MacCarthy’s birthplace at Castletownbere and meet Adrienne MacCarthy.

Connie Froude, from Ringwood, Hampshire, who visited MacCarthy’s Bar in April 2018, said: ‘I told Adrienne that our fathers had been in Nagasaki at the same time and her father had saved my father’s arm when it was poisoned during a medical drug experiment. I think that for both of us it was a very emotional experience and a few tears were shed.’

From Youghal, Co Cork, Larry O’Sullivan, as a 24-year-old prisoner in the same Nagasaki labour camp as Aidan – Fukuoka No 26 Camp, also known as Nagasaki No 2 – was one of four men used as guinea pigs. Each of them, injected with a substance but not told what it was or for what purpose, fell ill.

Larry did not become as seriously ill as the others, one of whom was near death, but his arm swelled up and turned black. One Japanese doctor had wanted to amputate the arm, but instead Larry underwent invasive treatment whereby his arm was slit open and the poison gouged out. There was no anaesthetic, and men had to sit on Larry's arms and legs to hold him down.

After the war, in an account of his wartime experiences he wrote for his four children, Larry, who died in 1997 aged 76, wrote: ‘While I was securely held by three burly prisoners, the Jap doctor sliced through the full extent of my forearm from elbow to wrist. The pain was simply indescribable as he slowly carved his way, inch by excruciating inch. Large lumps of rotten flesh fell out of the gaping wound and black blood flooded across the rough wooden table.’

Larry furiously banged his head on the table to try to knock himself out, but to no avail.

GHASTLY SCAR ALONG HIS ARM

However, the infection returned and, with a ghastly scar along his arm, Larry went to Aidan’s hut, which served as a sick bay. Aidan bathed the swollen arm, gently rubbing away any visible pus, and cleaned it with disinfectant. Pain lessened and Larry was able to return to work in the coalmine to which he was assigned. For the rest of his life, he always felt it was Aidan’s care that had saved his arm.

In April 1945, Larry had contracted pneumonia, which was rife in the camp. For days he drifted in and out of delirium in a sea of sweat. Dr MacCarthy came to examine him, confirming it was indeed pneumonia, but explaining there were no drugs he could give him, nothing to help, but that Larry had youth on his side.

There was no medication and little or no surgical instruments and a very limited supply of disinfectants, Larry recalled. Yet Aidan had an endless stream of men needing urgent medical care to a level he was unable to give. ‘Nevertheless, he achieved some remarkable results in the most primitive conditions, particularly on boils and other skin diseases among which the tropical killers were the most troublesome.’

Dr MacCarthy was ingenious in finding things to help. In a Red Cross parcel he found Barbisol, a shaving cream. He read the label and discovered an ingredient called salicylic acid. He knew this was the main constituent of aspirin, so was able to use the cream to tend wounds, adding it to Larry’s treatment to ease the pain and reduce pus and swelling.

DIGGING THEIR OWN GRAVES

Suddenly, In August 1945, it seemed the atmosphere in the camp had changed. The guards were more angry and vicious than usual and Larry and the other men began to think perhaps the time was up for Japan. They knew Germany had given up.

One day all the men in the camp were taken to an area and told to start digging. Even sick men, as long as they could stand, were forced to dig. It became apparent that it was a trench, long and deep. Japanese workmen came and built a wooden platform at one end and it was obvious the men were digging their own graves.

Larry looked along the line of men each side of the trench, so many familiar faces, including Dr MacCarthy, all there, digging for hours. The platform indicated that it would be for machine guns. Nothing happened immediately, and the men returned to their normal routine of trying to survive down the mines or in the shipyard with less and less food.

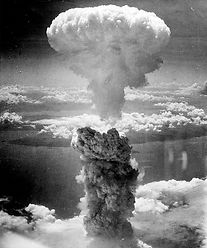

Then, on August 6, Larry emerged from his nightshift at the mine to see the A-bomb mushroom cloud above Hiroshima.

Three days later, with his arm septic once more, and Dr MacCarthy having warned him he might have to dig out the poison again, Larry was joining the queue of men waiting to see Aidan in his hut. Larry knew the instruments to work on his arm would have been fashioned by some of the men in the camp and, of course, there would be no anaesthetic. He prayed that today was not the day for this and that the wound could be cleaned and, hopefully, there would be some dressing for it.

FLASH OF A THOUSAND SUNS

‘Very few looked at the sky though there were murmurs of aircraft high above Nagasaki, some few miles away to the south-west,’ Larry wrote. ‘Then came the ‘flash of a thousand suns’, that terrible brightness which had devastated Hiroshima.’ With the blinding flash, there was a rumble, loud and deep, which to Larry felt like an underground explosion.

‘The shockwave took several seconds to reach us. The hills surrounding the city limited the extent of the blast and the searing heat. The trees on the hillside were neatly laid in rows, their foliage stripped. Wooden slats from our huts were sucked up and the sky became dark…’

Aidan and his patients ran into an air-raid shelter and waited until the rumbling stopped before stepping out to see what had happened. They looked towards the city unable to believe their eyes – Nagasaki had disappeared. They surveyed the scene in ‘mute amazement’.

Later, when Aidan announced the war was over, there was ‘stunned silence’ among the prisoners. ‘There were a few choked cheers,’ said Larry. ‘There were many tears on gaunt faces, but most men were on their knees thanking God for deliverance. I was one of these.

‘Practical steps were immediately taken to find food to supplement our totally inadequate rations. Groups of men, armed with Japanese weapons, scoured the immediate countryside in search of food, clothing and medication.’

RADIATION AND FALL-OUT DEBRIS

Aidan expressed ‘considerable reservations about giving arms to our men in case the weapons were used to avenge the barbarity of some of the Jap guards. He also emphasised the very serious hazards of wandering into areas heavily contaminated by radiation and fall-out debris.’

Over days and weeks, said Larry, Aidan set about trying to help the wounded and dying inhabitants of Nagasaki. Larry and other men fetched and carried for him and tried to find survivors in the smoking ruins. It was the most awful sight and the stench was overpowering but soon the prisoners-of-war would be free to go home.

When Larry returned home, he had another operation to re-open his wounded arm, clean it, and put veins back in place, some of which had been protruding.

Larry joined the Royal Navy at the age of 17 in 1938, taking with him the parting words of his Aunt Nora who advised him to say his prayers every night and ‘never talk to the English’. As a gunnery rating, he saw action in the Atlantic, North Sea, Indian Ocean and the English Channel. His final wartime assignment was on HMS Exeter, sunk during a battle with the Japanese navy in the Java Sea in February 1942, which was when he was taken prisoner.

Larry suffered from post-traumatic stress after the war, but there was a happy ending to his story. In an air-raid shelter in London, while on leave from the Navy, he had met a nurse, Bridie Lordan from Clonakilty, and though it was a brief encounter he was smitten and went in search of her after the war. He found her and in April 1947 they were married in Oxford (pictured below). They returned to Ireland to live at Clonakilty after Larry left the Navy in 1971.

‘Once I’d read the books, I knew I had to go to Castletownbere and see for myself where this amazing man had been born’

* Dr Aidan MacCarthy.

* Larry O'Sullivan.

By Connie Froude

My father wrote a book for the four of us, his children, and I think that for most of us that was when we found out just how bad things had been in the prison camp, and indeed before it, on the ships that he served on that had been sunk.

It’s not a big book, just pages of A4 that he typed out and sometimes not in great detail as it was too hard to allow himself to go back to those times, but it’s important to us as a family to know what those poor people suffered. Writing his book brought it all back to him, and it wasn't easy. Mum wasn't pleased he was doing it at all, and he couldn't talk to her about it.

When I was young, dad was still having nightmares about the camp. He would wake up screaming. As time went on it happened less and less but the experience was never far from his mind. Some men never talked about it, they couldn’t bear to think about what they’d seen and experienced but my father talked about it off and on. I hope it helped.

I think that writing the book helped him in a way, too. Yes, it brought back dreadful memories and stirred up those nightmares again but also there was a feeling that it was out of his mind and onto paper that he could put down or put in a drawer and leave, knowing that the information was there if we wanted to know.

I have talked about writing a book based on my father’s book for over twenty years and recently got round to actually doing some research. I noticed that my father had added some small notes by hand after the book had been typed out and he’d mentioned that the doctor who saved his arm, Dr MacCarthy, was from Castletownbere in Cork.

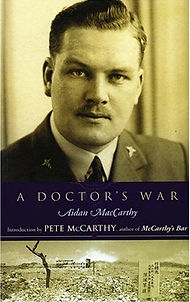

When I spoke to one of my brothers about it, he told me that Dr MacCarthy had written a book about his experiences in the war, including Nagasaki. I think I ordered that book within five minutes of hearing about it and having Googled it, I also read about Pete McCarthy and ‘A Doctor’s Sword’ and bought that, too.

Reading Dr MacCarthy’s account of Nagasaki was so similar to my father’s that in places I was able to read accounts of the same event side by side: the digging of the trench for example, where the men were to be machine-gunned when the Japanese realised they’d lost the war; and on the day the atomic bomb was dropped my father was joining the queue of men waiting to see the doctor and they all took shelter in the same air-raid shelter.

Once I’d read the books, I knew I had to go to Castletownbere and see for myself where this amazing man had been born. I’d read about Adrienne and Niki and the ceremonial sword and just wanted to let them know that my father had been a very grateful patient of their father.

CROSSING TO ROSSLARE

So, we booked our crossing to Rosslare and spent a few days in Clonakilty where my mother was born and where she and dad retired to in the late 1980s. We set off for what would have been a beautiful drive down to Castletownbere, had the sun decided to shine for more than five minutes of our entire holiday in Ireland, and found MacCarthy’s Bar within moments.

I hadn’t been able to contact anyone in the bar beforehand as it turned out that Adrienne had had problems with her phone for a few days, and I was quite worried that the pub might be closed for the day or something would prevent us from meeting them, and I wasn’t going to be the most popular person in the world if we’d made the trip for nothing!

However, I popped my head round the door and a friendly lady behind the bar told me that Niki was on holiday but Adrienne would be back after lunch. We had a little wander around the town and a bite to eat and went back to the pub a couple of hours later. There was Adrienne behind the bar talking to some people who’d obviously also come to talk about the PoW camps.

I waited until they’d gone and then walked up to the bar and told Adrienne that our fathers had been in Nagasaki at the same time and in fact her father had saved my father’s arm when it was poisoned during a medical drug experiment. I think that for both of us it was a very emotional experience and a few tears shed.

I also told her that I’d read ‘A Doctor’s War’ and ‘A Doctor’s Sword’ but, unfortunately, the film hadn’t been shown in England. She immediately gave me a copy of the DVD and invited us to come to her home upstairs where she showed us another DVD based on the original book which starts with Dr MacCarthy’s early years in Castletownbere and then to university and then to the war in France, and later of course, Japan.

It was a surreal experience, seeing on screen, in that lovely pub, with Adrienne, what I had grown up hearing about all my life.

Adrienne was so generous with her time and we were so happy that we’d met her, experienced that friendly pub and her kindness. To top it all, when we got downstairs into the pub again a small band began to play and we enjoyed singing along with everyone.

What an experience! I think I was buzzing for days!

A couple of days after we got home, the family all came around so we could watch ‘A Doctor’s Sword’ together. The story was fascinating and very moving. My children were lucky enough to know their grandparents well and knew of grandpa’s time in the PoW camp. Luckily, they had been able to enjoy many years with my father before he died and they found the film very educational and moving. We were emotionally drained afterwards.

Beautifully made, the film showed conditions as they were in the camps and the tragedies before them, too, at sea and on land. Life in the camp was portrayed exactly as I’d heard from my father and both he and Dr MacCarthy talked about the huge trench they had to dig, realising it was for their own graves.

It was also quite incredible to see Niki MacCarthy’s journey, which must have been hard to bear at times, but it was very interesting and handled with dignity. I have huge respect for Niki and how she handled her meetings in Japan and her respect for the people she met. They clearly respected her, too, and it was touching that the expert was able to demonstrate, by his use of words, that the camp commandant, in the end, put himself below that of the doctor.

* Dr Aidan MacCarthy.

* Dr Aidan MacCarthy.